No argument: the arts are essential, and that’s that.

Renée Fleming, Harry Lennix and Lindsay Jones walk the walk.

There's a saying we have posted on our kitchen fridge that says, "You need not attend every argument to which you are invited."

I thought about that when a colleague of mine – someone I’ve known for years, someone with a history of supporting the arts and advocating for artists – invited me into the "are the arts really essential" argument.

I declined.

It wasn't easy. This person pushed the buttons that could easily lead me to engage in this debate, like telling me that issues like pay equity, childcare, gun safety or climate change are all more important than the arts. How, they asked, could that be argued? In the face of those daunting challenges, are the arts actually essential?

That question has been asked repeatedly and answered definitively.

The answer is, without question, YES. And saying that addressing pay equity, childcare, gun safety and climate change are more important than supporting the arts is like saying that thinking, talking, breathing and running are more important than food. To effectively do the former, you need a healthy dose of the latter.

Disagree? Take a look at how successfully so many of our leaders (and voters) are addressing the pressing issues my colleague describes (spoiler alert: they’re not). Far too many berate and belittle, which does not inspire or persuade; engage in reactive rhetoric, which does not posses that power storytelling; and rely on data to counter propaganda, when the true parry to a bad or false narrative is a good and true one.

We need the arts to understand these differences, and to aspire to more true and honest ways of changing, charging and empowering ourselves and our relationships with others. The arts provide the rich nutrition that allows us to think more clearly, see more feelingly and collaborate more effectively. Without them, we rely on junk food masquerading as sustenance. With too little of them, we have become malnourished. And it shows.

No question, there are plenty of challenging conversations and a plethora of worthwhile debates to be had about how we create art, fund it, run not-for-profit arts organizations, produce for-profit work, handle workplace issues, explore critically important DEI issues and more. And yes, there are circumstances where it's not just helpful to be able justify the necessity of the arts throughout our society, it's necessary – lobbying elected officials about legislation impacting the sector, for example. We'll explore that and more in future newsletters, and I look forward to robust conversations about the processes by which artists, arts organization and arts supporters carry on.

But I don't think we have time for specious "are the arts really essential" arguments, especially when they're coming from inside the house. We know the arts are basic nutritional requirements for humanity. We see people that are hungry for them. They must be fed.

Here are three artists who are doing exactly that.

Renée Fleming isn't only one of the world's greatest singers and ambassadors, she's also a groundbreaking arts advocate.

In the company of Dr. Francis Collins and the National Institutes of Health, Renée created Music And Mind, an initiative that focuses on the intersection of music and neuroscience and spotlights music's extraordinary healing effect on people dealing with or recovering from an array of conditions, including stroke, dementia, depression and catastrophic brain injury. Renée often leads "Music And Mind" presentations when she's out of tour (and in fact will be doing one in Chicago on May 8 as part of The Chicago Humanities Festival).

I've known and worked with Renée for years, including producing the PBS Great Performances special Chicago Voices. She's frequently called “The People’s Diva," but to me she’s always been much more People than Diva. She thrives on collaboration, and you can see it in the way she shares stages, stories and spotlights with others.

She does so in her remarkable new book, Music And Mind, a curated collection of essays from leading scientists, artists, creative arts therapists, educators and health care providers about the powerful impacts of music and the arts on health and the human experience.

It is an extraordinary achievement. Wonderful essays by artists like Yo-Yo Ma, Anna DeVeare Smith, Ann Patchett, Ben Folds, Mark Morris and Rosanne Cash are juxtaposed with compelling and accessible pieces by scientists, therapists and musicologist like Daniel Levitan, Nina Kraus, J. Todd Frazier, Concetta Tomaino and Julene Johnson, all preceded by perfect prefaces from Dr. Collins and Renée herself.

I love Sting's description of this magnificent book. “When the bonds of our common humanity are being stretched to the limits at the same time as the intensifying stresses on our personal well-being," he writes, "Renee’s book is a reminder that music is the meta language that connects all individuals and spans all cultures religions and races period music has never been more important.” Amen, good sir.

You've got to read Music And Mind. You'll be both moved and wonderfully informed by the power of art to heal, and startled to consider how the arts, when better and more frequently utilized, could save the world billions of dollars in health care. The book is a perfect depiction of art as both means and ends, and Renée is the perfect embodiment of how to be both an artist and an advocate.

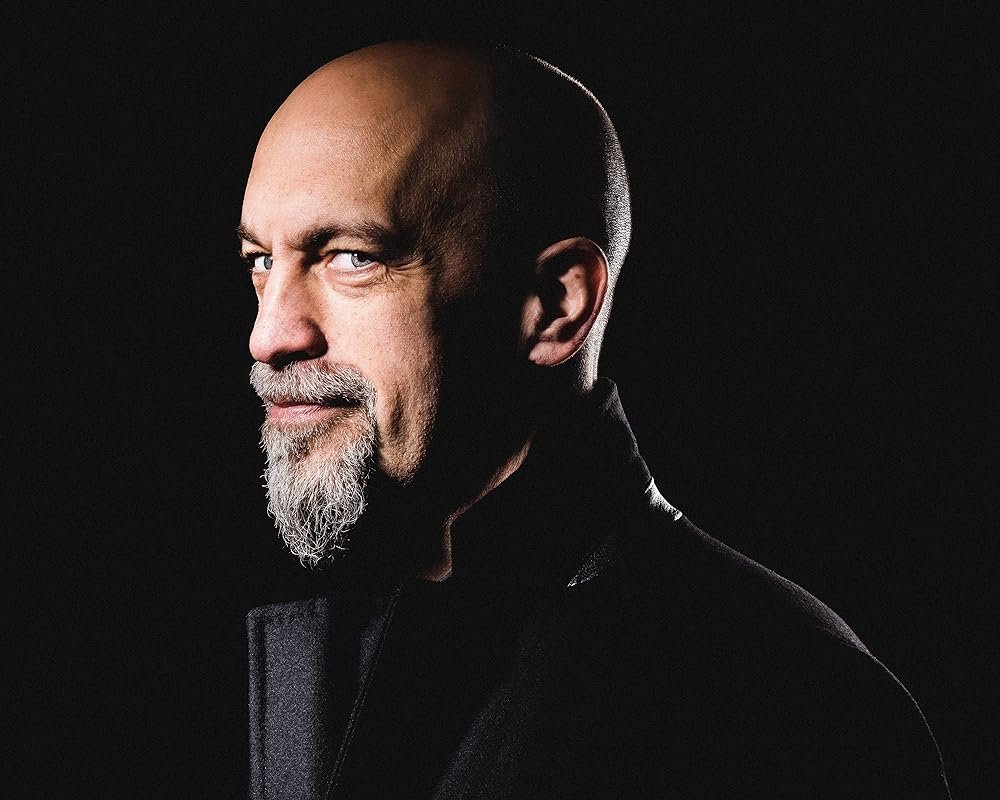

From the first time I saw Harry Lennix act (I believe it was an episode of ER), I've wanted to see, hear or read everything he does.

I’ve failed miserably in that quest (Harry is one prolific artist) but this spring I’ll get to see him not once but twice, in Steppenwolf’s Purpose and Congo Square’s How I Learned What I Learned.

My interest in and affection for Harry’s work has been intensified by the generous human behind it. Somewhere between all the gigs listed on his IMDB page, Harry has made time to walk the walk for causes he supports, the issues he believes in and the city from which he comes.

One of my favorite of these is the Lillian Marcie Center and African American Museum of The Performing Arts on Chicago’s South Side, something Harry has described as “the Black version of Lincoln Center.” I love big swings for the fences and admire the vision and leadership a project like this requires.

Harry's been a visionary and leader throughout his career, and the causes for which he has crusaded include health care (as Ambassador for the Prostate Cancer Foundation), education (serving on the Advisory Council for alma mater Northwestern University) and childhood literacy (as a board member for Reading Rescue, which serves at-risk elementary school kids by training educators who want to teach these kids reaching skills). He's also hit the campaign trail for candidates in which he believes, and I imagine that's at least partially because he knows that our elected reps make critical decisions that have a crucial impact our field.

That Harry considered a life in the priesthood before dedicating himself to the arts tells me a lot about a man clearly committed to something greater than himself. What a wonderful way to look at being both an artist and an advocate.

Composer, producer, sound designer, podcaster, performer, teacher and advocate Lindsay Jones is one of those guys who can certainly talk the talk (he is endlessly entertaining both in person and on social media) but who also walks the walk. His talent, currently on display in Northlight Theatre's current offering Brooklyn Laundry, is undeniable.

But it's how he does what he does that makes him a wonderful example of how to advocate for the arts. Lindsay finds genuine joy in celebrating the work of his fellow artists. He possesses a wonderful clarity about how an artist's work can not only entertains but also change how people feel about themselves.

Listen to the way he talks about his work in this wonderful interview. You'll hear the mix of intelligence, confidence and vulnerability that makes him so sought-after not just for gigs but as a guest for interviews, podcasts and lectures. He clearly treasures the interconnectedness of folks who dedicate their lives to theater and sees it as a way of inspiring people to dedicate their lives to each other.

I suspect this matters to Lindsay because of how the arts, and one arts teacher in particular, transformed his life. The Facebook post he wrote to mark that teacher's passing is so good, so full of grace and gratitude, so infused with humility and self-awareness, so steeped in appreciation for those who serve the world through teaching, so imbued with love for those who wish to transform people through art and such a lovely example of the power of good arts advocacy that I’m going to use it to end this edition of Arts in Action.

Enjoy, and see you again in a couple of weeks. Now take us home, Lindsay...

____

Within a traditional education structure, I have always been an incredibly bad student.

And yet, I’m an endlessly curious person who always wants to learn and have spent most of my adult life teaching and mentoring others. Why is that?

The reason is people like Barney Hammond.

Look, I’ll be honest: I barely graduated high school. They didn’t have a diagnosis of ADHD back then and when the only solution offered to me was “a good swift kick in the ass” (as one vice principal once said to me while standing very close to my face), I realized that perhaps formal education was not in my best interest.

With very few other options available, I managed to weasel my way into the Drama department of what was then called the North Carolina School Of The Arts as the state legislature that year mandated that all NC state universities must have at least 50% of the student population that were actually from North Carolina. I was accepted for a single probationary year in a class of 50 people and was told that my chances of making through to graduation were almost non-existent. As someone who would later be described as “a person who might make a good character actor in their later years”, I knew that I better make the best of whatever situation I could find, or I’d be bagging groceries while asking people about their record collection for the rest of my life.

The school’s faculty was largely made up of people who had no idea what to do with me, which I don’t blame them for as I had no idea what to do with me either. Most instruction was given to me through clenched teeth, and lord knows I tried my best.

Then I went into Barney Hammond’s class. Ostensibly, he was our Voice And Speech teacher, but he really was so much more than this. He showed me how to connect my voice to the body and how to really tap into the hidden vocal energy within me. He gave me the tools to break down a single line of text to find its meaning, and then break down entire monologues to find clarity in the thoughts behind them. He showed me that Shakespeare’s texts are not just hoity-toity language that meant nothing, but that each sentence carries deep meaning and emotion, and he also showed me how to find those things. All of these things gave me were gifts, and these gifts became the basis for my craft in being an actor. He literally gave me the tools to be an actor and pointed me in the direction of how I could use them.

But in addition to that, he showed me something that few other teachers have ever shown me: kindness and patience. Don’t get me wrong, he didn’t put up with any bullshit, he was there to DO THE WORK and you had better be there for the same reason. But he would accept you from whatever point of view that you were coming from and actually encouraged it (rather than try to beat it out of you), and that level of grace and commitment to me as an individual literally kept me from giving up every day.

Out of a class of 50 people from that first year, I was one of six that were allowed to come back for the next year to join a new class of 50 people. From those 50 people, I was one of 15 people to graduate at the end of another four years. Barney Hammond is one of the primary reasons that I made it to the end (and for the record, I barely graduated college as well - that’s another story.)

But then after I graduated college, a funny thing happened: I became a composer and sound designer. You’d think I’d leave all of that acting stuff behind when I switched to a new job, but actually all of these techniques that I learned from Barney are things I use in my job every day. I still have to figure out character and through-line and how a line reads and what it means, because I have to provide score and sound design that matches it. I still have to know how to assess a script for energy and pace. I have to be able to find the meaning in any line in a Shakespeare play so that I can make sure that the score supports it. Plus, I need to be able to understand how actors produce their speaking voice in a theatre, so I know how to best amplify it and then surround it with the right sound and music so that I can support it with the best emotional context possible. Everything, EVERYTHING I learned from Barney, I still use every single day.

Most importantly, that includes the part in treating people with kindness and grace and encouraging them to be the best version of themselves that they can be. Anytime I’m given the opportunity to teach anyone anything, this is what I lead with, because I want to give to others what Barney gave to me.

Even after Barney retired, he was incredibly supportive of all of his former students. I always felt a little self-conscious about not being an actor anymore, but he was always incredibly vocal in his support for me in my career and celebrated my victories as if they were his. I tried to express my gratitude to him a few times, but I don’t know if I was ever fully able to get it across how much I valued him and what he’d given me.

Yesterday, Barney quietly slipped away after a brief bout of pneumonia. By the time I learned he was sick, it was already too late to get a message to him to tell him how much I appreciated everything that he had given me. The best I can do is to carry forth what I’ve learned and pass it on to as many people as I can and try to make sure that they understand why it’s so important.

Thanks, Barney. Rest well.

If you're not currently a subscriber to Arts in Action but would like to make sure you don't miss future editions, click here.